Part 3: Death Valley – The Project Takes on Meaning

By this point in the development and production process, all of us knew that we had something very special. Yet despite the fact that we had filmed rehearsals and demonstrations of the drum parts, the backstage scene, and all of the song performances, there was still something missing. The interviews we had done to this point covered topics related to live performance, but did not address the bread-and-butter questions I had prepared in my many outlines about the individual drum parts. We needed to get together for yet another shoot, so Neil could actually discuss the songs.

From the outset, Neil wanted to do this in a spectacular natural setting, preferably outdoors, to give the show a cinematic quality, and give the viewer a break from the studio and stage environments of the performances. Several locations were discussed as we began to compare schedules, but we were looking at a window of available time in Neil’s calendar that put us smack in the middle of winter. Neil suggested Death Valley National Park as a suitable location, for its great natural beauty, and because the chances of rain spoiling the shoot were practically nil. Rob, Paul, and I were going to be in Southern California in January for the NAMM show anyway, so it was settled—we would rendezvous in Death Valley.

After flying into Las Vegas late at night, Paul, Rob, and I set out early the next morning, heading across the desert toward Death Valley—one of the most memorable and incredible experiences of my life. Of course I had read about and seen photos of Death Valley, but as with viewing any natural wonder, important piece of architecture, or famous painting, nothing compares to seeing it with your own eyes. From the moment we drove into the park, the breathtaking vistas and unbelievable colors had us all commenting to each other about how spectacular everything looked.

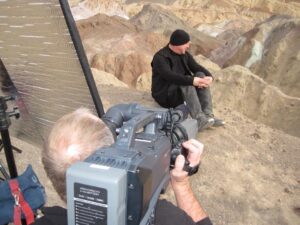

Armed with our map (cell phone and GPS signals don’t reach the area too well, which actually adds to the spirit of adventure of visiting the place), we drove through some scenic mountain and desert areas and finally found our way to the Furnace Creek Inn, where Neil had arrived the previous night. The Inn is a date-palm oasis, a green jewel in the barren, brown desert. The low-slung building is set halfway into the side of a mountain, and was built early in the 20th century, with scenic terraces and red tile roofs framing the formal dining room and windowed lobby. You could spend a couple of days just exploring the Inn itself. But after a very quick lunch with Neil, we mapped out a plan of attack for the next two days of shooting. Neil reviewed the questions and topics I had proposed as discussion points, added some tweaks and changes of his own, and we narrowed the topics down to focus on the truly unique and essential elements of each song’s drum part. The Hudson crew piled into our vehicles, and Neil mounted his motorcycle. Knowing the park well, Neil first led us to the general store and gas station in Furnace Creek, where everyone stocked up on snacks and drinks to get them through the day.

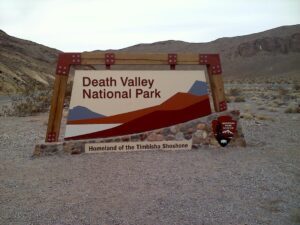

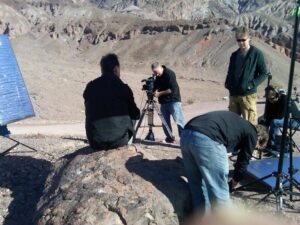

Then we headed for Artist’s Palette and Zabriskie Point, two vistas in the park that look like paintings made real. The desert presents a fantastic mosaic of colors that is completely unexpected until you experience it. As we began to capture footage of Neil discussing his drum parts in front of these breathtaking scenes, we realized that his idea of juxtaposing the timeless serenity of this natural setting with the lights and loud excitement of the concert was brilliant. As we proceeded with the filming, I was (along with Neil, it seemed) truly enjoying talking about his work on songs such as “Subdivisions,” “Limelight,” “Free Will,” “Far Cry,” and so many more.

As the light faded on the first day, we headed across the park to our hotel, located in a small village (actually more like a cluster of buildings) called Stovepipe Wells. To give you an idea of the scale of Death Valley, it took us over an hour to drive the two-lane road from Zabriskie Point to Stovepipe Wells. The motel was a compound of one-story, dark brown Western-style clapboard buildings, perfectly suited to the landscape—overlooking one of the only areas with actual sand dunes in Death Valley National Park (most of the landscape is rocky, not sandy). A cluster of mesquite trees overhung the restaurant, bar, and small common room at the center of the complex. When I entered my room, I immediately noticed there was no TV, no phone, and no clock. Perfect!

We relied on our cell phones (though they had no phone service) to check the time and set wake-up alarms each morning. After a fun dinner at the restaurant with the entire crew, including Neil, all sitting at a long table, eating together, and sharing stories, I couldn’t resist the temptation to walk off for about a half mile down the road, and then a few hundred yards off to the side of it, just to experience the dark of the desert. I have never seen that many stars in the sky, and I have never experienced that kind of enveloping blackness. What an amazing experience. I don’t know if there is anything out there that could have possibly attacked me, but I figured I would head back to my room before I found out.

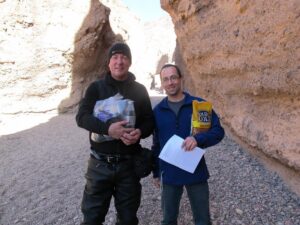

The second day of filming captured scenic footage of Neil riding along various park roads on his motorcycle, majestic scenes that would all be pieced together in the final program to create a movie-like quality. We headed to an area called the Natural Bridge, which involved a hike up a canyon to reach a bridge-like geological formation carved out by water. By this point Neil and I had done enough interviews that our exchanges became more conversational and more fun, as so often happens with two enthusiastic drummers talking about their craft. Rob, who had gone back to the general store to pick up lunch for everyone, returned as we headed back down the canyon to the cars. Seeing Rob hiking toward us like an overladen pack mule, Neil and I both grabbed a few items to help him out as we headed down the hill. One of my favorite photos from the trip is of Neil and me walking down the hill together, smiling and carrying bags of potato chips and pretzels. Neil gave that shot the perfect title: “Snack Boys.”

After lunch we continued down the snaking main park road to Badwater Basin, the lowest, driest, and hottest spot in North America. (Luckily, it was January, when it wasn’t so hot. I can only imagine what it must be like in summer, when temperatures can reach 120 degrees and more—the record is 138. It can truly be a life-threatening environment.)

After parking along the road overlooking the basin, we finally got a closer look at the salt flats we had been admiring from higher up. A rare rain had left a couple of inches of water in the center of the basin, making it look like a lake. Death Valley typically receives less than two inches of rain per year, and its surfaces are hard and impermeable, so a little moisture can linger for a while. As the water evaporates, it leaves behind the signature white color of the salt flats.

We decided we would get closer to the water so that the “lake” would be in the background behind Neil, with the mountains reflected on the surface. But as we walked out and downward toward the salt flat, we discovered that the evaporating water not only leaves behind white salt, it also leaves nice, deep mud. All of us began sinking up to our ankles as we tried to find the proper location to shoot. The crew had some two-by-fours, which Neil and the camera could stand on, and we were able to get what we needed. Fortunately none of us was swallowed by quicksand—although Dan came close.

From Badwater, at 282 feet below sea level, we could look up the sheer cliff face toward our next and final destination, Dante’s View—at an elevation of 5,475 feet. Although not more than a mile or so above us, the only way by vehicle would take us back to Furnace Creek, then slowly up the winding mountain road to the overlook point at the top. This trip would take us at least an hour, and the park ranger who had been supervising our shoot told us that snow had covered the road near the top, and it was closed by a locked gate. He thought maybe he could get us up there in his 4×4, perhaps with Greg’s crew in their Suburban, but our sedan and Neil’s motorcycle would be out of luck. Neil told us he would stop for gas in Furnace Creek, then meet us at the closed gate to wait for the ranger.

Paul, Rob, and I drove along for over an hour, passing the Inn at about the halfway point, and noticing the temperature getting gradually colder as we ascended into higher elevations. The road began to climb steeply, with signs pointing towards Dante’s View. We noticed little patches of snow on the ground, and came to the gate the ranger had told us about—but it was open, and none of the other guys were around. We parked by the side of the road and waited. After about thirty minutes, there was still no sign of anyone. Surely the ranger would have come down to get us if things were safe by now, wouldn’t he? And Neil said he had to stop for gas. Was he behind us or ahead of us? Without cell phone service, there was no way of knowing if he had attempted the snowy pass above, or even if he had fallen and been injured. Adding to all of this, the sun was beginning to get low in the sky, threatening to leave us without the final bits of shooting we needed. After another ten minutes we decided to go on ahead and see what had happened. As we neared the summit, slippery patches of snow covered the road. None of us being motorcycle riders ourselves, these patches looked much too dangerous for a bike to cross.

But Neil had just kept riding, tiptoeing through those snowy patches as far as the summit—all the while expecting to encounter a closed gate. Then, he wondered why no one else was there. Eventually Greg, Dan, and the guys followed him up in the Suburban, and captured some terrific shots of Neil riding up the final switchbacks of the road and pulling into the overlook at Dante’s View.

As we rode up, we saw that not only was everyone okay, but they were framing the final scene, just as we were beginning to lose light. Right on the precipice of Dante’s View sat Neil on his bike, while below him lay a stunning panorama of the whole of Death Valley. Here, as the sunset turned golden, Neil filmed the introduction to the entire DVD, on the last minute of the last day of the shoot, in which he summarized all the work that been done in the days, weeks and months before.

As soon as Greg called, “That’s a wrap,” Neil expressed concern about riding down through the icy passes, and immediately set off. The rest of us gathered our stuff and followed, while Greg and Dan stayed behind for a few minutes to capture the sun slipping down behind the Panamint Mountains across the valley. As Paul, Rob, and I descended in our car and finally came back down to the parts of the mountainside that were free of frost, we saw Neil sitting by the side of the road on his bike. Pulling up alongside, we rolled down the window to see if anything was wrong.

“Oh no,” he said, “just enjoying the moment.”

Then we could see that at this vantage point, the golden dusk had bathed the sky in all purple and pink, but still allowed a beautiful multicolored view of miles and miles of Death Valley and its surrounding mountains spread out below us. Neil smiled, and we left him with his thoughts and continued back to Stovepipe Wells.

That night we gathered for a final dinner, all of us sitting at the same long table. The occasion called for an extra glass of wine for all of us (which Neil added on top of, I suspect, a private Macallan or two in his room). Interestingly, Neil and I had both battled colds during the entire shoot, and one of our cameramen, Jeff, had experienced a serious bout of food poisoning on the first day, yet after the incredible experiences we had shared together over the past two days, all of this was forgotten about as we talked and laughed. When our drinks arrived, Neil raised his glass to toast and thank all of us, and to say that this trip and shoot was one of the most wonderful experiences of his life. I glanced at Paul and Rob, and saw that they were as deeply moved as I was.