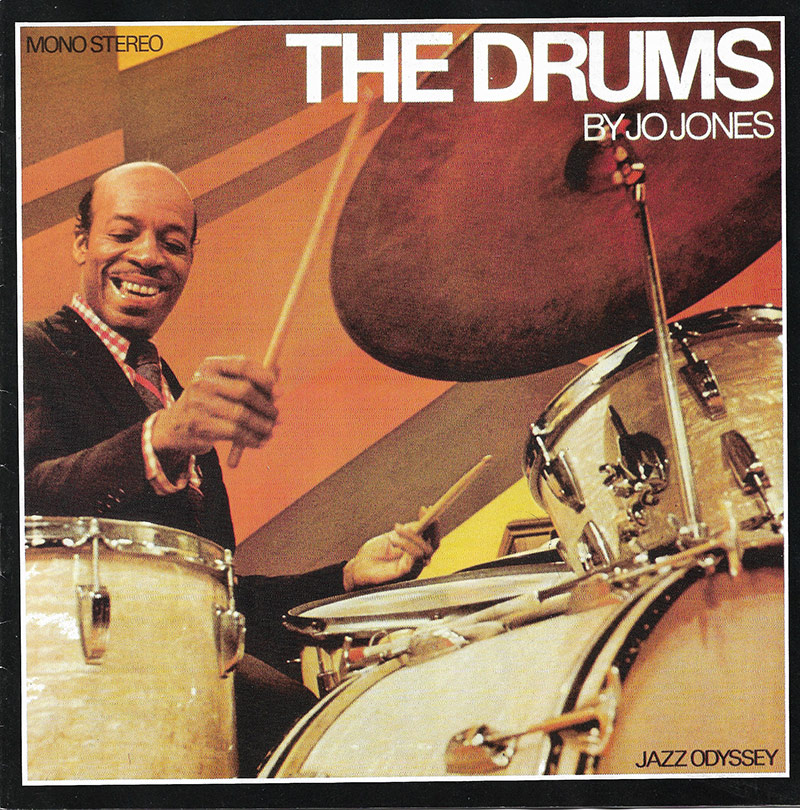

The Drums By Jo Jones, was the brainchild of long-time French jazz critic and champion of swing, Hugues Panassié. Though Panassie was the ultimate jazz purist–he detested be-bop and didn’t even believe that Benny Goodman played “real” jazz–he nonetheless loved Papa Jo and freely acknowledged Jo’s considerable contributions to the Count Basie band, to rhythm sections in general, and to jazz drumming in particular. What Panassie did was brilliant in its simplicity: Let Papa Jo loose in the studio with a drum set and a voice mike, and have him demonstrate and detail the styles of the drummers who influenced him, and the drummers who, in his estimation, influenced drumming. Those who knew the enigmatic Mr. Jones would tell you that it wasn’t often easy to decipher the meaning in Jo’s verbal parables and riddles, but fortunately, on this landmark recording, his meanings are relatively clear.

Also quite clear, then and now, is what Jo Jones meant to drumming. Basically, he changed the jazz drumming playing field from that of a sometimes leaden, four-square presence that emphasized a four-to-the-bar beat via the bass drum and snare drum, to that of a lighter, more interactive and musical timekeeper. Jo might not have invented the hi-hat or the ride cymbal per se, but he helped define how they should be played and how they would be played for years to come. As one quarter of what was called Basie’s “All-American Rhythm Section” from 1934 to 1948, with a few interruptions — Basie, bassist Walter Page, rhythm guitarist Freddie Green—Jo set the stage and laid the groundwork for drummers those we acknowledge today as the founding fathers of modern jazz drumming.

This recording finds Jo in his favorite setting: Telling stories and demonstrating the talents about the greats, the near greats, the long forgotten, from Krupa and Chick Webb, to Baby Dodds and Baby Lovett. The bonus track, from 1969, features Jo with another legend; stride piano giant Willie “The Lion” Smith. Their rendition of “Sweet Sue” is a beautiful example of two, wiley masters at work who had no need for a bass player, or any other player for that matter, to sound like an orchestra.

In 1973, Jo Jones–nicknamed “Papa” Jo in his later years to ensure he wasn’t confused with “Philly” Joe Jones–was 62 years old and had a legacy of contributions to jazz and jazz drumming behind him. Though acknowledged by musicologists as a percussionist who was virtually the father of modern jazz drumming, in 1973, he was something of a forgotten man in the United States, leading to episodes of depression that even his good friend and admirer, Buddy Rich, couldn’t talk him out of.

Still, Papa Jo had Europe, where he began to spend more and more time on tour, performing before audiences who adored him. He was particularly revered in France, the locale of this unique recording, where he was in the midst of a European tour with like-minded stylists that included keyboard giant Milt Buckner, and sometimes veteran swing tenor saxophonists like Buddy Tate and Illinois Jacquet.

Audio Recording | 4 Tracks | 77 minutes | Files are delivered via download as high-quality, AAC audio files.

Jo Jones

Born in Chicago, Illinois, Jones moved to Alabama, where he learned to play several instruments, including saxophone, piano, and drums. He worked as a drummer and tap-dancer at carnival shows until joining Walter Page‘s band, the Blue Devils in Oklahoma City in the late 1920s. He recorded with trumpeter Lloyd Hunter‘s Serenaders in 1931, and later joined pianist Count Basie‘s band in 1934. Jones, Basie, guitarist Freddie Green and bassist Walter Page were sometimes billed as an “All-American Rhythm section,” an ideal team. Jones took a brief break for two years when he was in the military, but he remained with Basie until 1948. He participated in the Jazz at the Philharmonic concert series.

Born in Chicago, Illinois, Jones moved to Alabama, where he learned to play several instruments, including saxophone, piano, and drums. He worked as a drummer and tap-dancer at carnival shows until joining Walter Page‘s band, the Blue Devils in Oklahoma City in the late 1920s. He recorded with trumpeter Lloyd Hunter‘s Serenaders in 1931, and later joined pianist Count Basie‘s band in 1934. Jones, Basie, guitarist Freddie Green and bassist Walter Page were sometimes billed as an “All-American Rhythm section,” an ideal team. Jones took a brief break for two years when he was in the military, but he remained with Basie until 1948. He participated in the Jazz at the Philharmonic concert series.

He was one of the first drummers to promote the use of brushes on drums and shifting the role of timekeeping from the bass drumto the hi-hat cymbal. Jones had a major influence on later drummers such as Buddy Rich, Kenny Clarke, Roy Haynes, Max Roach, and Louie Bellson. He also starred in several films, most notably the musical short Jammin’ the Blues (1944).

Jones performed regularly in later years at the West End jazz club at 116th and Broadway in New York City. These performances were generally very well attended by other drummers such as Max Roach and Roy Haynes. In addition to his artistry on the drums, Jones was known for his combative temperament.

One famous instance of his irritable temper was in the spring of 1936, when he threw a cymbal at a very young Charlie Parker – who had failed to improvise after losing the chord changes. Parker was in fact, inspired by this and went on to become arguably the greatest saxophonist ever.

In contrast to the prevailing jazz drum style exemplified by Gene Krupa‘s loud, insistent pounding of the bass drum on each beat, Jones often omitted bass drum playing altogether. Jones also continued a ride rhythm on hi-hat while it was continuously opening and closing instead of the common practice of striking it while it was closed. Jones’s style influenced the modern jazz drummer’s tendency to play timekeeping rhythms on a suspended cymbal that is now known as the ride cymbal.

In 1979, Jones was inducted into the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame for his contribution to the Birmingham, Alabama musical heritage. Jones was the 1985 recipient of an American Jazz Masters fellowship awarded by the National Endowment for the Arts.

Known as Papa Jo Jones in his later years, he is sometimes confused with another influential jazz drummer, Philly Joe Jones. The two died only a few days apart.

Jones died of pneumonia in New York City at the age of 73.